Must All Immigrants Be Heroes?

The stories of Lassana Bathily and Mamadou Gassama illustrate how acts of everyday heroism can lead to naturalization. But what about everyone else?

On January 9, 2015 Lassana Bathily went to work like any other day. He didn’t expect that that day would change his life.

A Malian immigrant, Bathily had arrived in France — legally — at the age of 16. He attended high school in Paris, and spoke French, but in 2009 his application for a French work visa was rejected. It took Bathily two years to regularize his situation, after filing a court case. In the meantime, he worked several tedious and precarious jobs: custodian, dishwasher, construction worker. After finally obtaining his official work papers, he was able to secure a steady job at a kosher supermarket in the far reaches of Paris’s 20th arrondissement: Hyper Cacher. `

The rest of the story is well-known. Around 1 pm on the afternoon of January 9, an armed Islamic terrorist entered the Hyper Cacher, killed four people and took the rest of the shoppers and employees hostage.

Bathily was working in the storage area of the supermarket. He went straight into action, guiding six shoppers, including a baby, into a hermetically sealed refrigerator, where they could wait out the crisis. He then escaped through an emergency exit. His detailed description of the building to police gave them the information they needed to navigate the building; he also gave the anti-terrorism brigade the keys to the building.

Bathily’s bravery earned him international recognition and interviews on French television. He was called “the hero of Vincennes” (the name of the suburb adjacent to the Hyper Cacher). Several days later, French President François Hollande awarded Bathily the ultimate prize: French citizenship.

Citizenship: that “holy grail” of the immigrant experience. Not everyone can be a hero, but sometimes it feels like acts of everyday heroism are the only way to gain this recognition in the eyes of the French state. For example, after the COVID-19 lockdown, French President Emmanuel Macron put in place an accelerated process for the naturalization of frontline workers, again suggesting that risking one’s life is the only proof of sufficient commitment to the country.

In general, access to citizenship in France is on the decline — part of a broader, global backlash against immigrants that even the country that “invented human rights” hasn’t been able to avoid. In a May 2021 tweet, former Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin praised the Macron administration for reducing naturalizations by 22 percent (the actual picture is more complex than a net reduction by one fifth). Despite some fluctuation, the overall trend is clearly negative. In 2004, more than 160,000 people received French nationality by decree. In 2023 — the year I was naturalized — that number was less than 100,000.

One Year Since Becoming French

Almost exactly one year ago, in late December 2023, I was walking along the boulevard de la Villette, in a drab part of Paris’s 19th arrondissement, when I received an email. “NATURALISATION,” the subject line read in all capital letters. It was a message I had been waiting to read for nearly two years.…

Under Macron, it seems that France has only raised the bar for excellence. On May 26, 2018, Mamoudou Gassama, also from Mali, scaled four stories of a burning apartment building in Paris’s 18th arrondissement to save a baby from a fire. Videos of this “French spiderman” went viral online. Four months later, Gassama obtained French nationality — of course, not without far-right leader Marine Le Pen taking the opportunity to call for a crackdown on all of the other “bad” immigrants committing crimes across France. Gassama now lives with his wife and baby in Montreuil and has a fixed work contract.

“Becoming French changed a lot of things for me,” Gassama said. “Now I have an identity card. I don’t work underground. I can travel, I can go wherever I want.”

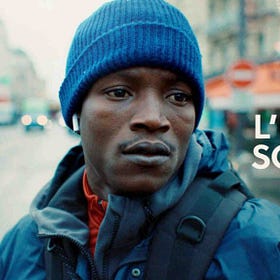

I’ve also written previously about Abou Sangaré, a Guinean mechanic who starred as the titular role for the movie “The Story of Souleymane.” For Sangaré, it was only after he starred in an award-winning film that he received his official papers not to work as an actor — but as a mechanic.

We Need More Stories Like Souleymane's

In the dark of the Sunday afternoon movie theater, there was a paralyzing silence. Even the two elderly white ladies who had talked throughout the previews were quiet. A name cloud with the film's actors flashed before the end credits began to roll. In the center, the name Abou Sangare appeared in bold lettering.

Of course, there is a double standard at play. In 2021, Pavel Durov, the founder of the messaging app Telegram, was awarded French citizenship after a few phone calls with Macron. More recently, a star rugby player was able to cut the queue in order to get naturalized.

What does this say about how we understand citizenship in the 21st century? Unfortunately, it would seem that like anything else, it’s become a marketplace where, apart from a few exceptions, the highest bidder wins.

But that was never the case for Bathily.

“As for me, I’ve always said that I felt French before I got the papers,” he said in an interview on the 10-year anniversary of his heroic action.

Edited by

.

I am curious how the influx of Americans is going to affect European immigration policies writ large in the next few years. Will having cash be sufficient to "become" European? We saw it in Portugal for a while, and now Spain has some slippery loopholes, but France seems to be more stringent than most. This is the paradox of a country that folks like you and me have come to love: we like being here because it remains distinctly French, and yet part of that distinct Frenchness comes with a host of problematic ideas about who is and isn't allowed or supposed to assimilate.