One Year Since Becoming French

The unnecessarily long story of how I ended up obtaining my French citizenship on the day of the Immigration Law and why I started this Substack.

Almost exactly one year ago, in late December 2023, I was walking along the boulevard de la Villette, in a drab part of Paris’s 19th arrondissement, when I received an email. “NATURALISATION,” the subject line read in all capital letters. It was a message I had been waiting to read for nearly two years. Maybe much longer.

I opened the email…

The beginning

People often ask me how I — a 31-year-old American — ended up living in France.

I grew up in New York City, then in Washington DC. My cultural references are, above all, American — and this despite an intensive period of Covid lockdown in which my partner and I screened all of the French cult classics from Les Bronzés font du ski to the collected works of Louis de Funès or the unwatchable La cité de la peur. I did my undergrad in Minnesota, and studied abroad in Cuba.

Why France, then?

That part of the story started on a boat crossing the English Channel in the late 1970s when my parents — both Americans — met for the first time. But that’s a tale for another post, and maybe another person (

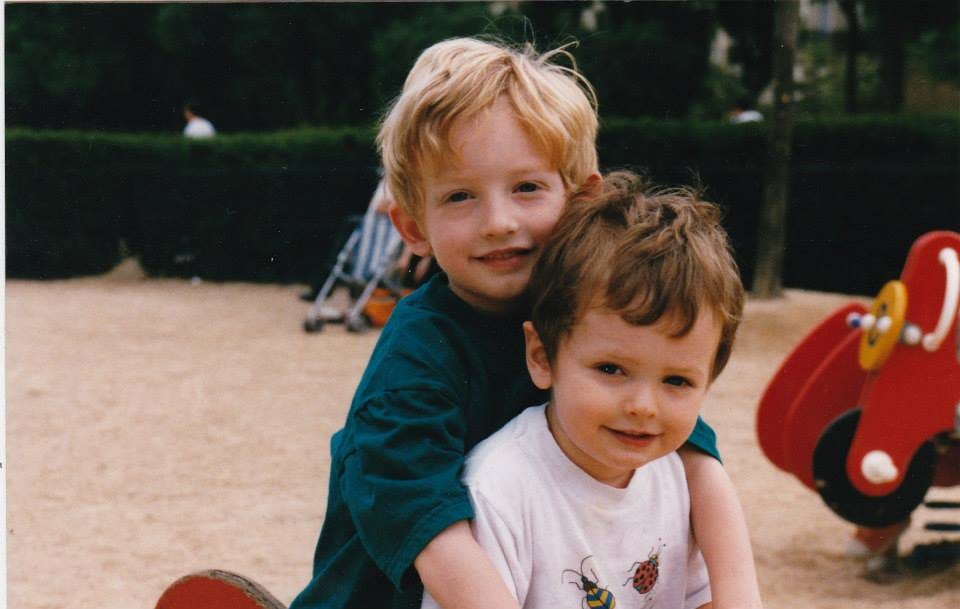

!), to write.I probably chose to move to France because the country was a key part of my childhood, the place where I formed some of my earliest memories. I first visited France as a three-year-old. That year — 1997 — my mom began teaching study abroad classes in Paris, first for Hunter College, then for Queens College in New York. We would come back every summer until 2003, when fears of a terrorism in the wake of 9/11 and the so-called “war on terror” slowed international travel. Then again starting in 2004.

The summers of my childhood were spent learning how to rollerblade underneath the elevated 6 metro line, drawing with my dad in parks, attending summer camps at the Ecole Bilingue in the 15th arrondissement and, later, going to parties and nightclubs in rural Champagne with French friends. Throughout this, France felt like a second home — a summer home that you pop into once in a while and dust the surfaces of before going back to your normal life.

That changed when I hit adulthood. In September 2015, I moved to Toulouse to teach English for a year. I had applied to several journalism jobs and internships, but lacking experience was rejected from all of them. Why not spend a year in La Ville Rose?

I came back to the States with the clarity that France was the place I wanted to live. There was something about the priorities — free time, social services, art — and the ideals — human rights, intellectual freedom, a culture of debate — of the country that suited me. The fact that you could live and get an education for a reasonable price didn’t hurt.

The French may often be difficult, but they’re difficult with good reason: they’re protecting something they hold dear.

I set my eyes on a grad school program in Paris, worked for a couple of years to save up money, and finally in 2018 moved here for good.

The envelope

After graduating from Sciences Po, where I studied journalism and international affairs, I decided to stay in France permanently. I’m not sure if applying for citizenship came across as an idea in a specific moment, or more so gradually as I became more integrated into French life.

In any case, by July 2022 I was ready to apply for citizenship. I had lived in France for four years: two in grad school and two on a work visa (plus the year in Toulouse). I had spent several weeks putting together all of my paperwork, and had even returned to New York for a friend’s wedding that doubled as a document-certifying trip.

On the last day of July — the day before I was scheduled to leave on my month-long (practically obligatory) August holiday — I spent the morning poring over the list of documents I needed to send in to the French authorities to start the process. These included, but were not limited to:

my birth certificate

my parents’ marriage certificate

several tax forms

college and graduate school transcripts

rental lease

passport and visa scans

several small passport-sized photos

an extra envelope (to send back my file in the case of missing documents)

I dutifully checked the printed boxes next to the documents on the list and the boxes I had written in above each one for the copies.

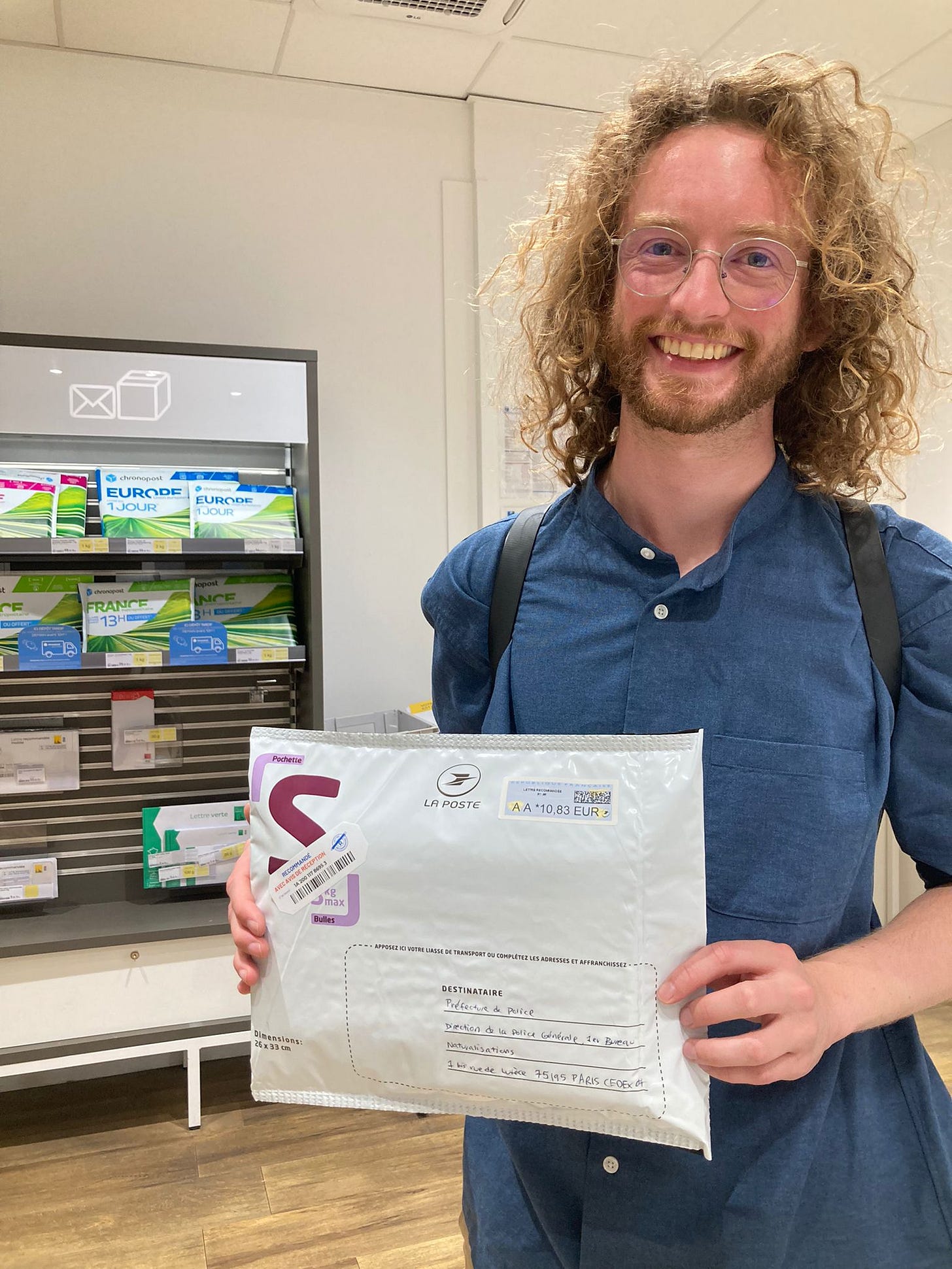

Not taking any chances, I asked my partner to take a video of me individually placing each document into a pre-paid return envelope the size of my face to prove that the application was, in fact, complete (surely something I had read on a messageboard somewhere).

In a photo she took that day, I’m smiling at the post office on the avenue Ledru-Rollin in the 12th before handing the package over to the bemused staff. I think the package weighed about the same as a newborn.

The waiting

Then began the long period of waiting. I think it was Fleetwood Mac who sang “the waiting is the hardest part,” though upon second thought it’s almost certainly Tom Petty. Regardless, I waited for a long time.

First, I waited six months for the French prefecture to verify that the documents were in order (if ever they hadn’t been, the prefecture wouldn’t have just asked for the missing document — too simple — they would have returned the entire stack with a note on top telling me what was missing: then, back to square one).

Then, I waited for the convocation to an interview. This second wait must have been several weeks or so. Finally, sometime in the spring of 2023, I was convened to the prefecture building on the Ile-Saint-Louis for an interview. I was ecstatic; I could almost smell the somewhat cheesy odor of French citizenship. I got together the additional documents requested to present on the day of the interview.

Two days before the interview, I received another email. The rendez-vous had been inexplicably canceled.

I waited a week and then emailed inquiring. The prefecture unapologetically wrote back with a new date and a new, significantly different list of documents to bring to the interview.

This time the appointment held.

The interview

The citizenship office at the Ile-Saint-Louis is located on a side street just meters from the part of the Seine that bifurcates around the tiny island. It’s a discrete building — a far cry from the imposing structure nearby where work and study visas are renewed.

The night before the appointment, I had reviewed my livret du citoyen, a dozen-or-so-page document with basic facts about French history and culture. I committed them to memory by writing all of the answers down in pen on a sheet of paper. There were facts about French geography (name France’s 12 overseas territories, the DOM-TOMs); about its history (who was Clovis?); and its laws (what are the two rights [droits] of French citizens, what are the three duties [devoirs]?).*

I packed this handwritten document in with the other requested files, and took a seat in the half-full waiting room.

The first thing I noticed about the citizenship section of the préfecture was the kindness with which I was received. Unlike at the main police precinct just across the street from the Notre-Dame cathedral — whose mostly West and North African immigrants can be seen waiting in a line that snakes out the door rain and shine — security smiled and made light-hearted jokes.

As an immigrant, you often feel like a square peg in a round hole. Sitting in the waiting room of the citizenship section in the morning quiet, I felt — for the first time in many years of administrative appointments — if not welcomed, at least respected.

When my name was called, Brigitte greeted me in her cubicle. Middle-aged with blonde hair, she reviewed my paperwork thoroughly, peppering me with questions. Many of the questions were about my French partner,

, who appeared on my rental lease as my “concubine” since we’re not married or in a civil union (or PACs). Brigitte asked me about my favorite monument (Le Panthéon) and the parts of France Diane had taken me to visit — to which I replied that quite possibly I had showed her more parts of France than she had shown me: Marseille, Toulouse, Albi, Perpignan, etc. She asked me about the types of food I liked to eat and what I liked to do with my French friends.If anything, the conversation felt weirdly more like an early therapy session or the first time meeting in the in-laws than a life-defining interview. But more than anything — for me at least — it felt like an inevitability, like the natural continuation of a process started long ago. I spoke French; I studied at a grande école; I grew up spending summers in French and spoke the language without too much of an accent. I was, for lack of a better word, destined to become French.

Toward the end, Brigitte stopped chit-chatting to ask me a few of the obligatory questions about French history. The questioning felt perfunctory: who was Charles de Gaulle? Name one person who was naturalized French. Name a French author. These were questions I could have answered in my sleep. Others, I’ve been told, were grilled a bit harder.

As we were walking out, Brigitte told me that if I didn’t hear anything in a few weeks, it most likely meant the application had been approved. (Only rejected citizenship applications are processed quickly.)

Unlike my drivers’ test, which I failed twice, I felt like I had nailed this one.

*The answers are: 1. Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique, La Réunion, Mayotte, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Wallis and Futuna, French Polynesia, New Caledonia and the French Southern and Antarctic Territories. 2. First King of France. 3. Right to vote and right to perform public functions. The obligation to respect the law, pay taxes and “contribute” to national defense.

The law

The naturalization email that appeared in my inbox as I walked along the boulevard de la Villette on that gloomy mid-December came from the préfecture’s access to French nationality branch (or SDANF).

“I have the pleasure to announce that you have acquired French nationality,” the email read, with additional information about next steps.

I sat down at the nearest café, stunned and a bit unbelieving. The email had taken a while to come through. In fact, for several weeks I had not seen any naturalization announcements in the French government gazette — the Journal Officiel. (I later learned that this temporary pause in naturalizations was not a figment of my imagination, but rather linked to the assassination of a schoolteacher in Arras by a foreign terrorist in late October.)

It was certainly an odd time to acquire French citizenship. For the past five years, and accelerating in the last couple, France — like many countries in Europe and around the world — has been swept up in a nativist anti-politics that wants to set the immigrant, the foreigner, the bi-national apart as somehow less than. In this politics, immigrants become the scapegoat for the unchecked neoliberalism and all-consuming digital technologies that are no less than destroying the fabric of society as we know it.

Fitting, then, that the day I finally obtained my French nationality coincided with the voting of France’s new Immigration Law. This law, which was passed with the express written consent of the far-right who later hailed it as an “ideological victory,” sought to make the conditions for entry into France more difficult. The law included provisions aimed at limiting family reunification, restricting health medical aid for undocumented immigrants and even make the requirements for applying for citizenship stricter.

The law was the magnum opus of former Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, freshly renamed Justice Minister in Macron’s new government this past week, and the pinnacle of President Emmanuel Macron’s capitulations to the far-right.

That night, instead of celebrating, I felt guilty. Guilty that, despite a couple of hiccups (the rescheduled appointment, the delays, the shifting set of documents), for me this process had been easy; guilty that because of my skin color and my background, nobody ever questioned my decision to become French; guilty that from this day forward, the French administration was set on making an already-complex process even more complicated for people who had fewer resources and knowledge of the system than I did.

How could I use my privilege to shed light on how the far-right was making life more difficult for foreigners living in France?

Starting a space for discussing Frenchness

I didn’t immediately start this Substack. On the day I obtained my nationality and France passed the Immigration Law, I took to Twitter to write a thread, in French, about my feelings. That thread struck a chord with more than 1,000 likes and hundreds of retweets.

In private, I received messages about people’s horrific experiences with the French naturalization process. Applications rejected for no clear reason. Suggestive questions asked to Arab women. Kafkaesque administrative lapses.

Some of my own friends — a Syrian refugee, an American artist, a Turkish expat — have also struggled to navigate this system, and have shared their experience with me.

I also began to read and think about the weight of French nationality: in a country that not too long ago ruled over an empire whose “civilizing mission” was to create miniature versions of France and French people all around the world, from Martinique to Algeria, what does it mean to adopt that nationality? Does Frenchness have to be so all-consuming so as to override other senses of national belonging? After all, the naturalization interview is still formerly called an “assimilation interview” in French administrative speak.

And how permanent is French nationality, really? During World War II, Vichy revoked citizenship from hundreds of thousands of Jews simply on account of their religion. More recent instances of terrorists having their nationality revoked have sparked this a renewed debate on the sanctity of French citizenship.

Anatomy of a deportation

On the morning of July 25, less than 48 hours before the opening ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympics, Timour, a 37-year-old Uzbek, boarded a plane at Charles de Gaulle airport. He wasn’t doing so voluntarily. Dubbed a “risk to public security,” Timour was being deported to a country he hadn’t stepped foot in for nearly 20 years.

My microscopic experience of obtaining French nationality and making this country my new home fits into a larger narrative arc — one that I’m still trying to unpack and understand. In a sense, this Substack has helped me to do this.

For the past several months, I’ve been speaking with experts on immigration, journalists who cover the topic and people who have had different experiences with the French administrative apparatus than I have.

In 2025, I’m hoping to take this a step further: I want to bring you more original content and reporting; audio from some of my interviews; and a space to share your own experiences about Frenchness — from the perspective of native-born or naturalized, “expat” or immigrant, asylum seeker or refugee. If you or someone you know has experienced the French immigration or naturalization system firsthand and would like to share that experience with me and my audience, I want to hear from you.

As I write in my bio, I started this Substack in June, just after Macron dissolved the Assembly. It was, as I wrote, a moment of great hope and frustration. In a sense, “a moment of great hope and frustration” would also accurately describe how I felt on that December day in 2023 when I received my French citizenship.

I didn’t throw a party, but I did launch a newsletter.